1.1 Elgesio pokyčių modeliai mityboje

Mitybos įpročių keitimas yra sudėtingas procesas, kuriam įtakos turi daugybė psichologinių, socialinių ir kognityvinių veiksnių. Mitybos intervencijų veiksmingumas priklauso ne tik nuo žinių apie sveiką mitybą perteikimo, bet ir nuo paciento pasirengimo keistis įvertinimo bei komunikacijos metodų pritaikymo prie individualių išteklių ir apribojimų. Šiuo tikslu taikomi elgesio pokyčių teorijomis ir modeliais pagrįsti metodai, leidžiantys tiksliai pritaikyti intervencijas prie individualių poreikių.

Šioje modulio dalyje pirmiausia aptariamas Prochaskos ir DiClemente transteorinis pokyčių modelis (TTM), kuris apibūdina pokyčių procesą kaip etapų seką: išankstinis apmąstymas, apmąstymas, pasiruošimas, veiksmas, palaikymas ir atkrytis. Supratimas, kuriame etape yra pacientas, leidžia efektyviau planuoti terapinę ir edukacinę veiklą.

Kita svarbi modulyje aptariama priemonė yra motyvuojantis interviu (MP) – komunikacijos metodas, orientuotas į kliento vidinės motyvacijos stiprinimą per empatišką klausymąsi, atvirų klausimų formulavimą, perfrazavimą ir apibendrinimą. MP metodai, tokie kaip OARS, taip pat DARNCATS koncepcijos, sudaro pagrindą veiksmingai paremti paciento / kliento sprendimą keisti mitybos įpročius.

Ypatingas dėmesys taip pat skiriamas edukacinio turinio pritaikymui prie paciento / kliento kognityvinio ir motyvacinio lygio, o tai ypač svarbu dirbant su asmenimis, kenčiančiais nuo psichikos sveikatos sutrikimų. Emocinių ir kognityvinių kliūčių šalinimas įgyjant mitybos žinias leidžia realistiškiau ir veiksmingiau planuoti intervencijas.

Modelinis požiūris į elgesio pokyčius, pagrįstas teorija, motyvacija ir individualizuotu bendravimu, yra veiksmingos dietologijos ir psichodietologijos praktikos pagrindas.

Prochaskos ir DiClemente transteorinis modelis

Psichologų Jameso Prochaskos ir Carlo DiClemente sukurtas Transteorinis pokyčių modelis (TTM) apibūdina procesą, kurį individai išgyvena įgyvendindami savo elgesio pokyčius. Šį modelį sudaro šeši etapai:

1. Išankstinis apmąstymas: asmuo nežino apie problemą arba nelaiko jos reikšminga. Jis neketina artimiausiu metu keisti savo elgesio.

Paciento pavyzdys: Janas, 45 metų vyras, sergantis depresija, vartoja daug perdirbto maisto ir nemato jokio ryšio tarp savo mitybos ir savijautos. Jis nesvarsto galimybės keisti savo mitybos įpročių.

2. Apmąstymas: žmogus pradeda atpažinti problemą ir svarsto galimybę ką nors pakeisti, bet vis dar dvejoja, įvertindamas privalumus ir trūkumus.

Pacientės pavyzdys: Ana, 30 metų moteris, turinti nerimo sutrikimų, pastebėjo, kad jos greito maisto dieta gali paveikti jos nuotaiką. Ji svarsto galimybę keisti savo įpročius, tačiau nerimauja, kad sveikas maisto gaminimas užims per daug laiko.

3. Pasiruošimas: asmuo priėmė sprendimą keistis ir pradeda planuoti konkrečius veiksmus, kurių bus imtasi artimiausiu metu.

Paciento pavyzdys: Marekas, 50 metų vyras, sergantis bipoliniu sutrikimu, nusprendė pradėti sveikiau maitintis. Jis ieško receptų ir planuoja apsipirkti sveiko maisto.

4. Veiksmas: asmuo aktyviai keičia savo elgesį, įprasdamas prie naujų, sveikesnių įpročių.

Paciento pavyzdys: Kasia, 25 metų studentė, serganti anoreksija, pradėjo reguliariai valgyti subalansuotą maistą ir vengti ribojančių dietų.

5. Palaikymas: asmuo tęsia naują elgesį ilgą laiką, stengdamasis išvengti senų įpročių grįžimo.

Paciento pavyzdys: Omekas, 40 metų vyras, sergantis obsesiniu-kompulsiniu sutrikimu, šešis mėnesius laikėsi sveikos mitybos, nepaisant stresinių situacijų darbe.

6. Atkrytis: grįžimas prie ankstesnio, nesveiko elgesio. Tai įprasta pokyčių proceso dalis, po kurios individas paprastai vėl pereina ankstesnius etapus.

Pacientės pavyzdys: Ewa, 35 metų moteris, serganti depresija, po trijų mėnesių sveikos mitybos vėl pradėjo vartoti per daug saldumynų, ypač prastos nuotaikos laikotarpiais.

Transteorinis pokyčių modelis (TTM) pabrėžia, kad elgesio keitimas yra procesas, kurio metu asmenys gali kelis kartus pereiti įvairius etapus, kol pasiekia ilgalaikius pokyčius. Šių etapų supratimas leidžia geriau paremti asmenis pokyčių procese, pritaikant intervencijas prie jų dabartinio etapo.

Transteorinis pokyčių modelis praktikoje

Socialinis darbuotojas gali naudoti Prochaskos ir DiClemente modelį (Transteorinis pokyčių modelis, TTM) kaip praktinę priemonę, skirtą padėti klientams, turintiems psichikos sveikatos sutrikimų, pokyčių procese, pavyzdžiui, laikytis sveikos mitybos, pagerinti miego higieną ar sumažinti psichoaktyviųjų medžiagų vartojimą. Pagrindinis šio modelio aspektas yra individualizuotas požiūris – tai yra, veiksmų pritaikymas prie kliento dabartinės būsenos.

1. Išankstinis apmąstymas – sąmoningumo ir pasitikėjimo kūrimas.

Šiame etape klientas nemato ryšio tarp savo elgesio ir patiriamų sunkumų – pavyzdžiui, jis gali neatpažinti savo mitybos poveikio psichinei sveikatai. Jis taip pat gali jaustis prislėgtas, prislėgtas arba nepasitikėti, kad pokyčiai gali atnešti kokių nors pagerėjimo.

Socialinio darbuotojo užduotis:

- Santykių kūrimas ir saugumo jausmo ugdymas.

- Švelniai nagrinėkite temą be jokio spaudimo.

- Subtiliai praplečiant kliento akiratį.

- Tikslas yra ne propaguoti pokyčius, o kurti ryšį ir pasitikėjimą bei ugdyti dvilypumą.

Venkite vertinimo ir spaudimo – tikslas yra ne įtikinti klientą keistis, o pasėti „apmąstymų sėklą“.

Dialogo pavyzdys

Kontekstas: Klientas – 45 metų Janas, kovojantis su depresija. Vizito metu jis skundžiasi lėtiniu nuovargiu ir energijos stoka. Jis pats neužsimena apie dietą.

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Jan, šiandien minėjai, kad nuolat jautiesi pavargusi ir jai trūksta energijos. Ar pastebėjai dienų, kai tas nuovargis šiek tiek sumažėjo?“

Janas: „Retai. Manau, kad visada jaučiuosi taip pat – išsekęs. Viskas dėl depresijos.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Žinoma, tai visiškai suprantama. Depresija tikrai gali būti labai sekinanti. Tiesiog iš smalsumo – ar visą dieną atkreipiate dėmesį į tai, ką valgote?“

Janas: „Ne visai. Ryte paprastai išgeriu tik kavos, o tada ką nors greito, pavyzdžiui, bandelę ar iešmelį. Vakare – traškučiai arba kažkas iš mikrobangų krosnelės.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Ačiū, kad pasidalinote. Aš neteisiu, tiesiog galvoju… Kartais mityba gali paveikti mūsų energijos lygį ir savijautą. Įdomu, ar kada nors susimąstėte apie šį ryšį?“

Janas: „Sąžiningai? Ne. Nemanau, kad tai ką nors pakeistų. Be to, neturiu energijos gaminti.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Tai irgi visiškai suprantama – maisto gaminimas reikalauja energijos, o būtent to jums trūksta. Tačiau kartais net ir nedideli pokyčiai gali šiek tiek pakeisti situaciją. Mums nereikia nieko daryti iš karto – galime tiesiog kartu aptarti temą, jei ir kada norėsite.“

2. Apmąstymai – sprendimų priėmimo palaikymas

Šiame etape klientas pradeda atpažinti ryšį tarp savo elgesio ir patiriamų problemų. Tačiau jis vis dar dvejoja – mato ir galimą naudą, ir baimes, susijusias su pokyčiais. Tai ambivalentiškumo, vidinio konflikto ir „įstrigimo“ jausmo etapas.

Socialinio darbuotojo vaidmuo:

- Kliento motyvacijos stiprinimas.

- Ambivalentiškumo išryškinimas ir pripažinimas kaip natūrali proceso dalis.

- Padėti klientui ištirti tiek pokyčių privalumus, tiek iššūkius.

Sudaryti klientui galimybių apmąstyti savo gebėjimus ir kartu nuodugniai aptarti savo baimes bei rūpesčius.

Dialogo pavyzdys

Kontekstas: 50 metų Marekas, sergantis bipoliniu sutrikimu. Jis nusprendė ką nors pakeisti ir ieško konkrečių žingsnių:

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Užsiminėte, kad norėtumėte sumažinti saldžių gėrimų vartojimą ir pabandyti valgyti daugiau daržovių. Kada, jūsų manymu, norėtumėte pradėti?“

Marekas: „Manau, nuo pirmadienio. Galbūt pusryčiams nusipirksiu šviežiai spaustų sulčių ir salotų.“

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Puikus planas! Ar jums reikia pagalbos? Galbūt galėtume sudaryti pirkinių sąrašą?“

Marekas: „Tai būtų puiku. Kartais vaikštau po parduotuvę ir galiausiai perku tuos pačius dalykus kaip ir visada.“

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Žinoma! Taip pat galime suplanuoti 2–3 greitus receptus, kuriems nereikia per daug energijos. Idėja ta, kad tai būtų įmanoma, o ne tobula.“

Dialogo komentaras:

Šiame dialoge socialinis darbuotojas:

- tyrinėja ir patvirtina klientės ambivalentiškumą, padėdamas jai jį įvardyti – parodydamas, kad įmanoma ir norėti pokyčių, ir jų bijoti tuo pačiu metu,

- pripažįsta saldumynų, kaip susidorojimo mechanizmo, vaidmenį, užuot juos įrėminus kaip kažką „blogo“,

- skatina ieškoti alternatyvų neatmetant dabartinių kliento strategijų,

- vartoja smalsų ir palaikantį požiūrį, sukurdamas erdvę tolesniam pokalbiui apie pokyčius.

Ambivalencija – vidinis konfliktas dėl pokyčių

Vienas iš pagrindinių psichologinių reiškinių, su kuriais susiduriama darbe, susijusiame su sveikatos elgsenos, įskaitant mitybos įpročius, pokyčiais, yra ambivalentiškumas. Tai natūrali vidinės įtampos būsena, kuri kyla, kai žmogus mato pokyčių naudą, bet tuo pačiu metu jų bijo arba atpažįsta sunkumus, kurie jį stabdo.

Ambivalencija nėra motyvacijos stokos požymis. Priešingai – ji dažniausiai pasireiškia žmonėms, kurie jau pradėjo svarstyti apie pokyčius, bet dar nėra pasirengę tam visiškai atsiduoti. Tai atspindi įtampą tarp noro tobulėti ir prisirišimo prie esamų įpročių. Pavyzdžiui, antsvorio turintis pacientas gali sakyti, kad nori sveikiau maitintis, bet tuo pačiu metu bijoti, kad nesusitvarkys su valgiaraščio planavimu ar atsisakys valgymo malonumo.

Ambivalencija kyla, kai naujas elgesys yra susijęs su netikrumu, pastangomis arba poreikiu paleisti kažką pažįstamo. Mūsų protas automatiškai įvertina riziką, komfortą, emocijas ir praeities patirtį. Žmonės, turintys nesėkmių istoriją, žemą savivertę ar lėtinį stresą, gali patirti ambivalentiškumą intensyviau ir ilgiau.

Ambivalentiškumo įveikimas nereiškia jo „pralaužimo“ jėga. Veiksminga strategija – padėti ištirti abi konflikto puses, gerbiant paciento sprendimus ir tempą. Tokios priemonės kaip motyvacinis pokalbis leidžia atsirasti vadinamiesiems pokalbiams apie pokyčius – teiginiams, kuriais pacientas išreiškia savo priežastis, norus, poreikius ir pasirengimą veikti.

Specialisto vaidmuo yra ne „įtikinti“ pacientą, o sukurti erdvę apmąstymams – kur žmogus galėtų suprasti, kad nors pokyčiai gali būti sunkūs, jie taip pat gali atnešti realų palengvėjimą, geresnę sveikatą ar didesnį veiksmų laisvės jausmą. Darbas su ambivalentiškumu dažnai yra pirmas ir svarbiausias žingsnis link ilgalaikių, sąmoningų pokyčių.

3. Pasiruošimas – išteklių planavimas ir stiprinimas

Šiame etape klientas jau yra priėmęs sprendimą keistis ir pradeda ruoštis konkretiems žingsniams. Jam gali prireikti pagalbos planuojant, organizuojant, vertinant savo gebėjimus ir nustatant turimus išteklius.

Socialinio darbuotojo užduotis:

- Bendradarbiaujant kuriant veiksmų planą.

- Kliento savarankiškumo jausmo stiprinimas.

- Padeda išsikelti realius, mažus tikslus.

Kliento sujungimas su papildomais ištekliais (pvz., paramos grupėmis, dietologu).

Dialogo pavyzdys:

Kontekstas: 50 metų Marekas, sergantis bipoliniu sutrikimu. Jis nusprendė ką nors pakeisti ir ieško konkrečių žingsnių.

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Užsiminėte, kad norėtumėte sumažinti saldžių gėrimų vartojimą ir pabandyti valgyti daugiau daržovių. Kada, jūsų manymu, norėtumėte pradėti?“

Marekas: „Manau, nuo pirmadienio. Galbūt pusryčiams nusipirksiu šviežiai spaustų sulčių ir salotų.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Puikus planas! Ar jums reikia pagalbos? Galbūt galėtume sudaryti pirkinių sąrašą?“

Marekas: „Tai būtų puiku. Kartais vaikštau po parduotuvę ir galiausiai nusiperku tuos pačius daiktus kaip ir visada.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Žinoma! Taip pat galime suplanuoti 2–3 greitus receptus, kuriems nereikia per daug energijos. Svarbiausia, kad tai būtų įmanoma, o ne tobula.“

Dialogo komentaras:

Šiame etape socialinis darbuotojas:

- kartu su klientu sukuria konkretų planą, remdamasis kliento idėjomis ir galimybėmis,

- sustiprina kliento veiksmų laisvės jausmą (pvz., „Puikus planas!“),

- siūlo praktinę, realistišką pagalbą, pavyzdžiui, pirkinių sąrašą, kuriame aptariami galimi kliento organizaciniai ar pažintiniai sunkumai,

- palaiko bendradarbiavimo ir įgalinimo toną – darbuotojas seka kliento tempą.

4. Veiksmai – pokyčių palaikymas – klientas aktyviai diegia naują elgesį. Tai intensyvių pastangų etapas, dažnai lydimas baimės būti teisiamam, netikrumo ir bandymų susidoroti su nesėkmėmis ar atkryčiais.

Socialinio darbuotojo vaidmuo:

- Pažangos stebėjimas ir pagalbos teikimas įveikiant iššūkius.

- Padėti kurti kliūčių įveikimo strategijas.

- Pripažinti ir švęsti net ir mažas sėkmes.

Pripažinti ir švęsti net ir mažas sėkmes.

Dialogo pavyzdys:

Kontekstas: 25 metų Kasia serga anoreksija. Pastarąsias dvi savaites ji laikosi plano valgyti tris kartus per dieną.

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Kasia, matau, kad laikaisi plano. Kaip tau tai atrodo?“

Kasia: „Truputį keista. Turiu daugiau energijos, bet nuolat galvoje nerimauja, kad priaugsiu svorio. Kasdien kovoju su savimi.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Tai didžiulės pastangos, ir labai svarbu, kad apie tai kalbėtumėte. Ar yra konkrečių paros laikų, kai jums sunkiausia?“

Kasia: „Vakarais. Tada po valgio jaučiu didžiausią kaltės jausmą.“

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Galbūt galėtume pabandyti sugalvoti ką nors, kas galėtų padėti tais laikais – kokią nors paramą ar būdą atitraukti dėmesį nuo sunkių minčių?“

Dialogo komentaras:

Šiame etape socialinis darbuotojas:

- pripažįsta kliento pažangą, o ne sutelkia dėmesį į sunkumus,

- normalizuoja ambivalentiškus jausmus (baimę, nerimą), pripažindamas juos natūralia šio etapo dalimi,

- išlaiko šiltą, empatišką toną, parodydamas, kad emocinė pokyčių pusė yra tokia pat svarbi kaip ir praktinė.

- pereinama prie bendradarbiavimo strategijų nagrinėjimo, o ne prie jau paruoštų patarimų siūlymo,

5. Palaikymas – pokyčių tvarumo palaikymas: klientas įtvirtina naujus įpročius ir mokosi susidoroti su pagundomis bei rizikos veiksniais. Tikslas – užkirsti kelią atkryčiui ir sustiprinti pokyčių tvarumą.

Socialinio darbuotojo vaidmuo:

- Situacijų, kurios gali išprovokuoti atkrytį, nustatymas.

- Teigiamų pokyčių rezultatų sustiprinimas.

Padėti rengiant nenumatytų atvejų planus ir prisitaikymo strategijas.

Dialogo pavyzdys:

Kontekstas: Tomekas, 40 metų, sergantis obsesiniu kompulsiniu sutrikimu. Jis 6 mėnesius laikėsi sveikų mitybos įpročių.

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Tomekai, jau pusė metų! Ką manai apie šį pasiekimą?“

Tomekas: „Gerai. Netgi pradėjau sau gaminti. Bet bijau, kad jei darbe kas nors nutiks ne taip, grįšiu prie senų įpročių.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Labai svarbu, kad jūs tai žinotumėte. Ar norėtumėte, kad kartu suplanuotume, ką galėtumėte daryti krizinėje situacijoje?“

Tomekas: „Taip. Būtų puiku turėti kažkokią „avarinę strategiją“.“

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Puiku. Tai galėtų būti konkretus sąrašas dalykų, kuriuos galite padaryti, arba žmonių, kuriems galite paskambinti. Pokyčių palaikymas taip pat reiškia žinojimą, kaip susidoroti su sunkumais, kai viskas klostosi ne taip puikiai.“

Dialogo komentaras:

Šiame etape socialinis darbuotojas:

- pripažįsta ir švenčia kliento sėkmę, stiprindamas jo motyvaciją tęsti pastangas,

- natūraliai, be baimės ar spaudimo, pereina prie atkryčio prevencijos,

- padeda klientui numatyti galimą riziką (pvz., „o kas, jei kils stresas?“),

- siūlo sukurti avarinį planą, kuris sustiprintų kliento kontrolės jausmą ir pasirengimą sudėtingesnėms akimirkoms.

6. Palaikymas – pokyčių tvarumo palaikymas: klientas grįžta prie ankstesnio elgesio. Atkrytis nėra nesėkmė, o natūrali pokyčių proceso dalis. Svarbiausia yra požiūris, pagrįstas empatija, supratimu ir skatinimu toliau dirbti su savimi.

Socialinio darbuotojo vaidmuo:

- Recidyvo normalizavimas kaip proceso sudedamoji dalis.

- Sustiprinti kliento iki šiol pasiektus pasiekimus.

Padėti analizuoti atkryčio priežastis ir planuoti tolesnius veiksmus.

Dialogo pavyzdys:

Kontekstas: 35 metų Ewa serga depresija. Po trijų mėnesių ji vėl pradėjo persivalgyti saldumynų.

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Užsiminėte, kad pastaruoju metu sugrįžo kai kurie seni įpročiai. Kaip dėl to jaučiatės?“

Ewa: „Kaip nesėkmė. Po visų tų pastangų vėl esu toje pačioje vietoje. Galbūt tiesiog nesugebu pasikeisti.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Ewa, tai ne nesėkmė – tai proceso dalis. Daugelis žmonių patiria atkryčius. Svarbu tai, kad tu tai pastebėjai ir atėjai čia apie tai pasikalbėti.“

Ewa: „Bet jaučiuosi beviltiškai.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Tai labai žmogiškas jausmas. Galbūt galėtume kartu pabandyti suprasti, kas nutiko ir kas galėtų padėti tau pradėti iš naujo? Nereikia pradėti nuo nulio – dalis darbo jau atlikta.“

Dialogo komentaras:

Šiame pavyzdyje:

- atkrytis nelaikomas nesėkme, o normaliu proceso etapu,

- socialinis darbuotojas vartoja empatišką ir normalizuojančią kalbą (pvz., „Tai proceso dalis“),

- perkelia dėmesį nuo „vėl patyriau nesėkmę“ į „kas jau pasiekta“,

- skatina grįžti prie veiksmų nereikalaujant neatidėliotinų pokyčių – taip sukuriama erdvė motyvacijos atkūrimui.

Prochaskos modelis dirbant su asmenimis, turinčiais valgymo sutrikimų – ką sako tyrimas?

Dirbant su asmenimis, kenčiančiais nuo valgymo sutrikimų, tokių kaip anoreksija ar bulimija, dažnai susiduriama su situacijomis, kai klientas nesijaučia pasiruošęs gydymui arba neatpažįsta problemos. Nors liga turi rimtų pasekmių tiek psichinei, tiek fizinei sveikatai, daugelis asmenų nenori arba negali pradėti pokyčių. Būtent todėl Prochaskos transteorinis pokyčių modelis gali būti ypač naudingas socialiniame darbe su šia grupe (Hasler ir kt., 2004).

Valgymo sutrikimų klinikoje atliktame tyrime dalyvavo 88 pacientės, kurioms buvo diagnozuota anoreksija, bulimija ir kiti valgymo sutrikimai. Buvo įvertintas kiekvieno asmens pasirengimo pokyčiams etapas (pvz., išankstinis apmąstymas – problemos nesuvokimas, apmąstymas – ambivalentiškumas, veiksmas – aktyvūs bandymai keistis). Šiuo tikslu buvo naudojama specializuota savęs vertinimo skalė (URICA). Be to, tyrimo metu buvo vertinama, ar pacientės taiko konkrečius pokyčius skatinančius metodus, pavyzdžiui, atpažina emocijas ar perima naują elgesį.

Paciento pokyčių stadija nepriklausė nuo jo amžiaus, ligos trukmės ar ankstesnio gydymo.

Tačiau svarbu buvo tai, ar asmuo kreipėsi pagalbos savo iniciatyva – pacientai, kurie tai darė savanoriškai, buvo labiau motyvuoti keistis.

Kuo emociškai labiau pacientai buvo įsitraukę į pokalbius apie savo problemas ir kuo aktyviau bandė ką nors pakeisti, tuo didesnė tikimybė, kad jie pereis į vėlesnius, labiau pažengusius pokyčių etapus.

Vien ankstesnis gydymas motyvacijos nepagerino, o tai pabrėžia, kaip svarbu dirbti konkrečiai su pačia motyvacija, o ne tiesiog siūlyti bendrą paramą (Hasler ir kt., 2004).

Ką tai reiškia socialiniam darbuotojui?

- Motyvacija keistis yra atskira tema, kurią reikėtų atpažinti ir puoselėti kliente – nepriklausomai nuo to, ar jis anksčiau lankėsi terapijoje, ar ne.

- Socialinis darbuotojas turėtų stebėti kliento elgesį: ar jis stengiasi keistis? Ar atsiveria emociškai? Ar aktyviai ieško paramos?

- Naudinga pritaikyti pokalbius ir intervencijas prie kliento dabartinės būsenos (vadovaujantis Prochaskos modeliu).

- Dėmesys su sutrikimu susijusioms emocijoms gali padėti klientui judėti į priekį – emocinis įsitraukimas gali būti svarbus žingsnis pokyčių link.

Tyrimas rodo, kad pokyčiai prasideda ne nuo veiksmų, o nuo pasirengimo, kuris vystosi palaipsniui per etapus. Net jei klientas dar nėra pasiruošęs, mes galime jį paremti šiame procese – pokalbiais, bendru planavimu ir padėdami emociškai apdoroti sunkumus.

INTERAKTYVI VEIKLA 43

| Bibliografija |

| Prochaska, J. O., ir DiClemente, C. C. (1984). Transteoretinis požiūris: tradicinių terapijos ribų peržengimas. Homewood, IL: Dow Jones-Irwin. Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., ir Norcross, J. C. (1992). Ieškant būdų, kaip žmonės keičiasi: taikymas priklausomybę sukeliančiam elgesiui. American Psychologist, 47(9), 1102–1114. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.47.9.1102 Prochaska, J. O., ir Velicer, W. F. (1997). Transteoretinis sveikatos elgsenos pokyčių modelis. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12(1), 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-12.1.38 |

1.2. Motyvuojančio pokalbio koncepcija

Motyvuojantis interviu (MP) – tai pokalbio metodas, padedantis asmenims keisti savo įpročius, ypač susijusius su sveikata. Jo tikslas – sustiprinti paciento vidinę motyvaciją – paskatinti jį keistis taip, kad jis pats to norėtų. Užuot nurodinėjęs žmogui, ką jis turėtų daryti, pokalbį vedantis asmuo padeda jam pačiam prieiti prie savo išvadų (Miller, 2022; Miller ir Rollnick, 2013).

Šį metodą devintajame dešimtmetyje sukūrė Williamas R. Milleris. Iš pradžių jis buvo naudojamas dirbant su nuo alkoholio priklausomais asmenimis, tačiau vėliau kartu su Stephenu Rollnicku Milleris išplėtė šį požiūrį, kad padėtų žmonėms, turintiems kitų sveikatos problemų, tokių kaip nutukimas, hipertenzija, diabetas ir fizinis neveiklumas (Miller, 2022; Cole ir kt., 2023).

Tradiciniuose pokalbiuose apie sveikatą dažnai susiduriame su tokiais pamokomais teiginiais kaip:

a) „Tau reikia liautis gerti tiek daug energinių gėrimų – jie tau kenkia.“

b) „Turėtumėte valgyti daugiau daržovių, antraip turėsite sveikatos problemų.“

Motyvuojančiame pokalbyje taikomas kitoks metodas. Užuot dėstęs, pokalbio vedėjas padeda pacientui pačiam suvokti, kad pokyčiai yra naudingi. Vietoj konfrontacijos dėmesys sutelkiamas į supratimą, empatiją ir bendradarbiavimą (Miller, 2022; Cole ir kt., 2023).

✅ „Ką manote apie savo mitybos įpročius? Ar matote ką nors, ką norėtumėte pakeisti?“

✅ „Kokios naudos, jūsų manymu, gautumėte, jei gertumėte mažiau energinių gėrimų?“

Dėl šio požiūrio pacientas nejaučiasi verčiamas daryti ką nors, o pats prieina prie išvados, kad verta keistis (Miller, 2022; Miller ir Rollnick, 2013).

Kur naudojamas motyvacinis pokalbis?

Nors iš pradžių jis buvo taikomas daugiausia priklausomybės terapijoje, šiandien jis naudojamas daugelyje sričių, pavyzdžiui:

- Gyvenimo būdo medicina – pvz., mitybos ir fizinio aktyvumo pokyčių palaikymas.

- Klinikinė psichologija – pvz., terapija asmenims, sergantiems depresija ar nerimo sutrikimais.

- Dietologija – pagalba žmonėms išsiugdyti sveikesnius mitybos įpročius.

- Širdies reabilitacija – pagalba pacientams po širdies smūgio keičiant gyvenimo būdą.

Dėl savo veiksmingumo šį metodą įvairios sveikatos organizacijos rekomenduoja kaip veiksmingą būdą padėti žmonėms pakeisti savo įpročius (Cole ir kt., 2023).

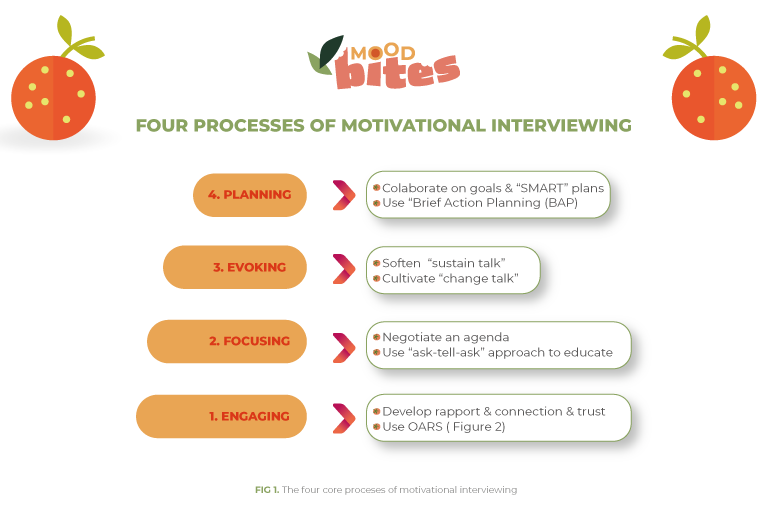

Keturi motyvacinio pokalbio procesai

1.2.1 Įsitraukimas

Pirmasis motyvuojančio pokalbio (MP) žingsnis yra įsitraukimas – užmegzti tvirtus, pasitikėjimu grįstus santykius su asmeniu, kurį norime paremti. Tikslas – sudaryti pacientui įspūdį, kad jis gali mumis pasitikėti ir kad mes nesame tam, kad jį teistume ar spaustume. Tik tada, kai žmogus jaučiasi suprastas ir priimtas, jis yra labiau linkęs pradėti pokalbį apie savo įpročių keitimą. Trys pagrindiniai metodai, padedantys įsitraukti į paciento veiklą, yra šie:

- Aktyvus klausymasis – nuoširdaus susidomėjimo rodymas jų jausmais ir mintimis.

- Atviras bendravimas – vengti uždarų klausimų, į kuriuos galima atsakyti tik „taip“ arba „ne“.

- OARS įrankiai – tai bendravimo technikų rinkinys, palaikantis ryšį ir motyvaciją.

OARS įrankiai – tai bendravimo technikų rinkinys, palaikantis ryšį ir motyvaciją.

Aktyvus klausymasis reiškia skirti visą dėmesį žmogui, su kuriuo kalbate. Svarbu ne tik išgirsti jo žodžius, bet ir suprasti, ką jis iš tikrųjų nori išreikšti. Taip pat svarbu parodyti empatiją – parodyti, kad suprantate jo jausmus, jų neteisdami.

Ką pasiekia aktyvus klausymasis?

✔️ Padeda sukurti pasitikėjimą ir saugumo jausmą.

✔️ Parodome kitam žmogui, kad jis mums svarbus.

✔️ Suteikia pacientui jausmą, kad jį išklauso, o ne verčia pamokslauti.

🔹 Jei kas nors sako, kad negali laikytis sveikos mitybos:

✅ „Matau, kad tau tai labai sunku. Norėčiau geriau suprasti, kaip dabar jautiesi.“

🔹 Jei pacientas mano, kad bandė, bet niekas nepadeda:

✅ „Girdėjau, kad jaučiatės labai nusivylę – jau išbandėte skirtingus metodus, bet vis tiek sunku laikytis sveikos mitybos.“

🔹 Jei kas nors jaučia, kad prarado valgymo kontrolę:

✅ „Ar teisingai suprantu, kad jaučiasi taip, lyg valgymas išslystų iš kontrolės?“

🔹 Jei pacientas pasidalija savo sunkumais:

✅ „Labai vertinu tai, kad atvirai apie tai kalbate. Tai labai svarbu ir reikia drąsos apie tai kalbėti.“

🔹 Jei kas nors sako, kad depresija atima motyvaciją keistis:

✅ „Žinau, kad keisti įpročius gali būti sunku, ypač kai depresija sukelia energijos trūkumą.“

🔹 Jei kas nors sako, kad jaučiasi prislėgtas:

✅ „Ačiū, kad pasidalinote tuo su manimi. Tai turi būti labai sunku, ir aš suprantu, kodėl jaučiatės taip kupini emocijų.“

Svarbu prisiminti, kad įsitraukimas yra pirmas žingsnis siekiant veiksmingo pokalbio – pacientas turi jausti, kad gali mumis pasitikėti. Aktyviai klausydamiesi galime parodyti klientui, kad jį suprantame, o tai skatina jį tęsti pokalbį. Palaikantys atsakymai parodo klientui, kad jo jausmai yra svarbūs ir kad jis nėra teisiamas.

Atviras bendravimas – kaip užduoti tinkamus klausimus?

Atviras bendravimas – tai pokalbio vesti būdas, skatinantis kitą asmenį laisviau kalbėti apie savo patirtį ir jausmus. Svarbiausias elementas – atviri klausimai – į kuriuos negalima atsakyti vien „taip“ arba „ne“. Šie klausimai skatina klientą apmąstyti ir kalbėti apie tai, kas jam svarbu.

Dėl to pacientas:

a) can speak openly about their difficulties,

b) pradeda apmąstyti savo įpročius,

c) mano, kad jų nuomonė ir emocijos yra svarbios.

Užduodami atvirus klausimus, pacientas pradeda mąstyti apie savo situaciją ir dažnai pats žengia pirmuosius žingsnius pokyčių link. Atviri klausimai laikomi veiksmingu būdu pagilinti problemos supratimą ir padėti nustatyti galimus sprendimus.

Kokie klausimai padeda pacientams apmąstyti pokyčius?

🔹 Užuot klausus: „Ar jums sunku valgyti, kai jaučiate stresą?“

✅ Geriau paklausti: „Kokios situacijos verčia jus griebtis maisto, net kai nesate alkanas?“

🔹 Užuot klausus: „Ar valgote pusryčius?“

✅ Geriau paklausti: „Kaip paprastai atrodo jūsų rytas? Ar turite laiko pavalgyti?“

🔹 Užuot klausus: „Ar norite gerti mažiau energinių gėrimų?“

✅ Geriau paklausti: „Ką manote apie tai, kiek energinių gėrimų paprastai suvartojate?“

🔹 Užuot klausus: „Ar pagalvojote apie mitybos keitimą?“

✅ Geriau paklausti: „Kas galėtų padėti jums maitintis sveikiau?“

Čia pateikiamas atvirojo ir uždarojo tipo klausimų palyginimas lentelės formatu:

| Atviras klausimas | Uždaras klausimas | Paaiškinimas (gauta papildoma informacija) |

|---|---|---|

| Kaip atrodo jūsų tipinė diena, kalbant apie valgymą? | Ar reguliariai valgote? | Leidžia pacientui apibūdinti savo dienos ritmą, nustatyti alkio laikus ir valgymo įpročius, pateikiant išsamesnį savo gyvenimo būdo vaizdą. |

| Kaip jaučiatės po valgio? | Ar valgymas veikia jūsų nuotaiką? | Suteikia įžvalgų apie emocines ir fizines reakcijas į maistą ir atskleidžia pasąmoninius ryšius tarp emocijų ir valgymo. |

| Kas padeda išlaikyti sveikus įpročius, o kas juos apsunkina? | Ar jums sunku išlaikyti sveikus įpročius? | Padeda pacientui atpažinti savo stipriąsias ir silpnąsias puses, taip pat kas jam padeda arba trukdo palaikyti sveiką elgesį. |

| Kokia jūsų patirtis bandant pakeisti savo mitybą praeityje? | Ar bandėte anksčiau keisti savo mitybą? | Atveria erdvę ankstesnių bandymų, nesėkmių priežasčių ir galimų sėkmės veiksnių analizei ateityje. |

| Kas nutinka, kai stresinėmis akimirkomis jaučiate stiprų norą valgyti? | Ar valgote, kai patiriate stresą? | Suteikia gilesnį supratimą apie su stresu susijusius valgymo modelius, nustato su stresu susijusius veiksnius ir alternatyvias įveikos strategijas. |

| Kokias emocijas jaučiate valgydami vienas, palyginti su tuo, kai valgote su kitais? | Ar jums labiau patinka valgyti vienam, ar su kitais? | Padeda atskleisti, kaip socialinis kontekstas veikia valgymo įpročius ir kokios emocinės reakcijos yra susijusios su skirtingomis situacijomis. |

| Kokios, jūsų manymu, didžiausios kliūtys keičiant mitybos įpročius? | Ar jums sunku pakeisti savo mitybos įpročius? | Suteikia pacientui erdvės tyrinėti ir išsakyti konkrečius iššūkius bei apsvarstyti savo sprendimus. |

| Kas vieną dieną valgymo metu palengvina, o kitą apsunkina? | Ar būna dienų, kai sunkiau laikytis sveikos mitybos? | Skatina apmąstyti kasdienius sunkumus ir padeda nustatyti veiksnius, kurie įtakoja sveikos mitybos paprastumą ar sunkumus. |

| Kas, jūsų manymu, galėtų padėti jums valgyti reguliariau? | Do you know what you could do to eat more regularly? | Ragina pacientą apsvarstyti realias, asmenines valgymo reguliarumo gerinimo strategijas, o ne pateikti greitą ar paviršutinišką atsakymą. |

OARS įrankių naudojimas – kaip efektyviai bendrauti ir palaikyti pokyčius

OARS yra keturių pagrindinių įgūdžių rinkinys, naudojamas motyvuojančiame pokalbyje. Juos galima laikyti įrankiais, padedančiais „išgauti“ žmogaus mintis, jausmus ir motyvaciją veikti. Šie metodai veda pokalbį taip, kad kitas asmuo jaustųsi išgirstas, suprastas ir labiau motyvuotas keistis.

ORAS sudaro:

✅ O – Atviri klausimai

✅ A – Patvirtinimai

✅ R – Apmąstymai

✅ S – Santraukos

Pavyzdys:

❌ Uždaras klausimas: „Ar maitinatės sveikai?“

➡️ Atsakymas: „Taip“ arba „Ne“ – pateikiama mažai arba visai nepateikiama jokios informacijos.

✅ Atviras klausimas: „Ką manote apie savo mitybos įpročius?“

➡️ Galimas atsakymas: „Kartais stengiuosi sveikai maitintis, bet dažnai valgau greitą maistą, nes neturiu laiko gaminti.“

O – (Open- ended questions) Atviri klausimai

Kaip minėta anksčiau, atviri klausimai yra tie, į kuriuos negalima atsakyti vien tik „taip“ arba „ne“. Jie skatina asmenį apmąstyti savo įpročius, jausmus ir sprendimus.

Šio tipo klausimai skatina gilesnį mąstymą ir leidžia asmeniui ištirti savo situaciją, o ne tiesiog atsakyti į iš anksto nustatytus raginimus ar klausimus.

A – Afirmacijos (teigiamas pastiprinimas / patvirtinimas)

Afirmacijos yra trumpos, teigiamos pastabos, padedančios sustiprinti žmogaus pasitikėjimą savimi ir savivertę. Užuot kritikavę ar nurodę klaidas, mes sutelkiame dėmesį į kito žmogaus pastangų, stipriųjų pusių ir vertybių išryškinimą.

Teiginių pavyzdžiai:

✅ „Matau, kad stengiatės sveikiau maitintis – tai puikus žingsnis!“

✅ „Vertinu jūsų sąžiningumą kalbant apie savo sunkumus. Tam reikia drąsos.“

✅ „Išties įspūdinga, kad nepaisant kovos su depresija, pastaruoju metu jums pavyko pasigaminti keletą sveikų patiekalų.“

Šios technikos taikymas:

- Suteikia žmogui motyvacijos toliau siekti pokyčių.

- Parodo, kad net ir maži žingsneliai yra prasmingi ir vertinami.

- Didina įsitraukimą į pokyčių procesą, sustiprindamas pastangas ir pažangą.

R – (Reflections / Paraphrasing) Apmąstymai / Perfrazavimas

Apmąstymai – tai kalbėtojo pasakyto teksto kartojimas, bet šiek tiek kitaip, siekiant parodyti supratimą ir patikslinti prasmę. Ši technika padeda pacientui jaustis išgirstam ir suprastam. Kartais, išgirdus savo mintis, suformuluotas kitaip, žmogus gali atpažinti įžvalgas ar modelius, kurių anksčiau nepastebėjo.

Teiginių pavyzdžiai:

✅ „Matau, kad stengiatės sveikiau maitintis – tai puikus žingsnis!“

✅ „Vertinu jūsų sąžiningumą kalbant apie savo sunkumus. Tam reikia drąsos.“

✅ „Išties įspūdinga, kad nepaisant kovos su depresija, pastaruoju metu jums pavyko pasigaminti keletą sveikų patiekalų.“

Naudojant šią techniką:

- Parodytumėte kalbėtojui, kad jūs tikrai jo klausotės.

- Padeda jiems geriau suprasti savo mintis ir jausmus.

Palengvina galimų problemos sprendimų paiešką.

S – Santraukos

Apibendrinimas reiškia svarbiausių pokalbio teiginių surinkimą ir jų pateikimą trumpa, aiškia forma. Tai padeda kalbėtojui pamatyti, dėl ko jau susitarta ir ką galima daryti toliau.

Santraukų pavyzdžiai:

🗣️ Pacientas: „Neturiu laiko gaminti, valgau skubėdamas ir dažnai griebiuosi saldumynų, nes jie pagerina savijautą.“

✅ Santrauka: „Taigi sakote, kad laiko trūkumas verčia jus rinktis greitus užkandžius, o saldumynai laikinai pakelia nuotaiką. Galbūt verta paieškoti greitų, bet sveikesnių alternatyvų?“

🗣️ Pacientas: „Žinau, kad turėčiau valgyti daugiau daržovių, bet man nepatinka jų skonis ir nežinau, kaip jas paruošti.“

✅ Santrauka: „Taigi, jums rūpi sveikesnė mityba, bet daržovių skonis ir nežinojimas, kaip jas paruošti, yra kliūtys. Galbūt galėtume kartu rasti keletą receptų, kurie jums atrodytų patrauklesni?“

Naudojant šią techniką:

- Padeda organizuoti pokalbį ir sutelkti dėmesį į pagrindinius klausimus.

- Parodo pacientui, kad jis buvo aiškiai suprastas.

Gali būti atspirties taškas tolesnei diskusijai apie galimus sprendimus.

Santrauka – kodėl OARS yra veiksmingas?

| Technique | Kas tai? | Pavyzdys |

|---|---|---|

| O – Atviri klausimai | Klausimai, į kuriuos reikia atsakyti ilgiau | „Ką manote apie savo mitybos įpročius?“ |

| A – Patvirtinimai | Teigiami komentarai, kurie stiprina motyvaciją | „It’s great that you’re making an effort to eat more vegetables!” |

| R – Atspindžiai | Kartojant tai, ką kažkas pasakė, kitais žodžiais | „Neturite daug laiko, todėl dažnai griebiatės jau paruošto maisto.“ |

| S – Santraukos | Svarbios informacijos rinkimas ir tvarkymas | „Iš to, ką sakote, atrodo, kad norite sveikiau maitintis, bet maisto gaminimas jums yra iššūkis.“ |

Naudodamas šias technikas, klientas ne tik jaučiasi geriau suprastas, bet ir pradeda atpažinti sprendimus, kuriuos gali įgyvendinti pats.

OARS technikos yra labai naudingos ne tik dirbant su klientais, bet ir kasdieniuose pokalbiuose. Jas galima naudoti bendraujant su:

✔️ Šeima – siekiant atidžiau išklausyti artimuosius ir juos paremti sunkiose situacijose.

✔️ Draugais – siekiant geriau suprasti jų emocijas nepriverčiant jų duoti patarimų.

✔️ Mokytojais ar klasės draugais – siekiant, kad pokalbiai būtų atviresni ir sąžiningesni.

OARS naudojimo kasdieniame gyvenime pavyzdžiai:

🗣️ Užuot klausus: „Kodėl tu toks liūdnas?“

✅ Geriau: „Matau, kad kažkas tave neramina. Ar norėtum apie tai pasikalbėti?“

(Atviras klausimas + aktyvus klausymasis)

🗣️ Užuot sakęs: „Nesijaudink, viskas bus gerai.“

✅ Geriau: „Tau tai turbūt labai sunku. Dėkoju, kad tuo su manimi pasidalinai.“

(Patvirtinimas + empatija)

🗣️ Užuot sakęs: „Tau tiesiog reikia daugiau mokytis.“

✅ Geriau: „Ar teisingai suprantu, kad jautiesi priblokštas medžiagos kiekio?“

(Apmąstymai / Perfrazavimas)

🗣️ Užuot sakęs: „Tai ką dabar darysi?“

✅ Geriau: „Iš to, ką pasakei, atrodo, kad mokyklinis stresas tave tikrai slegia. Kokie žingsniai galėtų padėti geriau jį valdyti?“

(Santrauka + problemų sprendimo skatinimas)

Dėl OARS naudojimo pokalbiai tampa natūralesni, o kitas žmogus jaučiasi tikrai išklausytas ir suprastas. Šias technikas verta naudoti ne tik profesinėje aplinkoje, bet ir kasdieniuose santykiuose – nes kiekvienas nori jausti, kad jo emocijos ir mintys yra svarbios.

1.2.2. Fokusavimas

Šiame pokalbio etape svarbu padėti pacientui nuspręsti, į ką jis nori sutelkti dėmesį. Tikslas yra ne pasakyti jam, ką jis turėtų daryti, o paklausti, kas jam svarbiausia.

Šis etapas yra labai svarbus, nes:

- Klientas pats pasirenka pokalbio temą, o tai padidina jo įsitraukimą.

- Mes neprimetame pokyčių, bet padedame nustatyti sritį, kuriai labiausiai reikia dėmesio.

- Mes netaisome ir nekritikuojame kliento, o kartu ieškome geriausio būdo pokyčiams.

Svarbu vengti „atstatymo reflekso“. Dažnai, kai matome, kad kažkas daro ką nors nesveiko, jaučiame norą nedelsdami tai atkreipti į mus ir pasakyti, ką jie turėtų daryti kitaip. Tačiau toks požiūris gali priversti kitą žmogų pasijusti teisiamu ir tapti gynybiniu.

❌ Blogas pavyzdys: „Turėtumėte valgyti daugiau daržovių, nes jūsų mityba nėra pakankamai maistinga.“

✅ Geresnis požiūris: „Kaip manote apie savo mitybą? Ar yra kokių nors maisto produktų, kuriuos norėtumėte valgyti dažniau?“

Šiame etape svarbu, kaip užduodame klausimus, kurie padeda apibrėžti tikslą. Žemiau esančioje lentelėje pateikti klausimų, kurie padeda klientams apibrėžti tikslą atsižvelgiant į jų nurodytą mitybos problemą, pavyzdžiai.

🔹 Jei pacientas turi apetito problemų:

✅ „Iš to, ką sakote, suprantu, kad būna dienų, kai neturite apetito, o kitomis – kai valgote daug. Apie kurį savo valgymo aspektą norėtumėte pakalbėti pirmiausia?“

🔹 Jei pacientas turi keletą skirtingų sunkumų:

✅ „Susiduriate su keliais su valgymu susijusiais iššūkiais. Ar norėtumėte sutelkti dėmesį į valgymo reguliarumą, ar galbūt į maisto kokybės gerinimą?“

🔹 Jei pacientas kenčia nuo nerimo:

✅ „Ar yra kokių nors konkrečių situacijų, kurios apsunkina sveiką mitybą, pavyzdžiui, kai nerimo simptomai pablogėja?“

1.2.3. Evoking

Motyvacijos žadinimas yra vienas svarbiausių motyvuojančio pokalbio etapų. Tikslas – padėti kalbėtojui pačiam atrasti savo pokyčių priežastis, o ne versti jį tai daryti. Kai žmogus pats pripažįsta, kodėl gali būti verta ką nors savo gyvenime patobulinti, jis labiau linkęs jaustis nuoširdžiai motyvuotas imtis veiksmų.

Šiame etape naudojami du metodai:

✅ „Kalbų apie pokyčius“ – teiginių, kuriais išreiškiamas noras ar ketinimas tobulėti, – sustiprinimas.

Kalbos apie pokyčius ir kalbos apie palaikymą – ką tai reiškia?

Pokalbis apie pokyčius – tai bet kokie teiginiai, rodantys, kad pacientas galvoja apie pokyčius arba nori daryti ką nors kitaip. Šio tipo teiginius reikėtų sustiprinti ir skatinti, kad pacientas galėtų juos toliau tyrinėti.

✅ Pokalbio apie pokyčius (noro veikti) pavyzdžiai

🗣️ „Norėčiau numesti svorio, nes manau, kad jausčiausi geriau.“

🗣️ „Manau, kad jei vakare valgyčiau mažiau, ryte turėčiau daugiau energijos.“

🗣️ „Man reikia pakeisti savo mitybą, nes tai pradeda mane veikti.“

🎯 Kaip sustiprinti pokalbį apie pokyčius:

✅ „Tai skamba kaip svarbus žingsnis jums. Kas jus skatina tai pakeisti?“

✅ „Kas, jūsų manymu, galėtų padėti jums įgyvendinti šį pokytį?“

❌ Palaikymo pokalbio (prisirišimo prie dabartinių įpročių) pavyzdžiai:

🗣️ „Aš visada valgau vakarais, tai tiesiog mano būdas atsipalaiduoti.“

🗣️ „Neturiu laiko gaminti sveikų patiekalų.“

🗣️ „Žinau, kad tai nesveika, bet aš mėgstu saldumynus ir nenoriu jų atsisakyti.“

🎯 Kaip sušvelninti palaikomąją kalbą be kritikos:

✅ „Matau, kad vakarinis valgymas suteikia jums komforto jausmą. Gal manote, kad yra kitų būdų pasiekti panašų efektą?“

✅ „Jums trūksta laiko maisto gaminimui – tai visiškai suprantama. Ką manote apie idėją ruošti maistą iš anksto kelioms dienoms?“

Kaip užduoti klausimus, kurie sustiprina pokalbį apie pokyčius

📌 Užuot klausus: „Ar žinai, kad saldumynai yra nesveika?“

✅ Geriau paklausti: „Ką gautum, jei sumažintum saldumynų kiekį savo mityboje?“

📌 Užuot sakęs: „Turėtumėte valgyti mažiau greito maisto.“

✅ Geriau paklauskite: „Kaip jaučiatės pavalgę greito maisto? Ar norėtumėte ką nors pakeisti?“

📌 Užuot klausus: „Kodėl negaminate namuose?“

✅ Geriau paklausti: „Kas jums galėtų palengvinti maisto gaminimą namuose?“

Skatinti kalbėti apie pokyčius

Miller ir Rollnick (2013) nustatė septynias kalbėjimo apie pokyčius kategorijas, kurias galima prisiminti naudojant akronimą DARNCATS. Šios kategorijos išsamiai aprašytos toliau pateiktoje lentelėje.

| Category | Description | Paciento pareiškimo pavyzdys |

|---|---|---|

| D – (Desire) Troškimas | Noras keistis | „Norėčiau geriau pavalgyti.“ |

| A – Ability (Gebėjimas) | Gebėjimas keistis, jausmas, kad tai įmanoma | „Manau, kad jei pabandysiu, galėsiu sveikiau maitintis.“ |

| R –Reasons (Priežastys) | Priežastys keistis | „Jei numesiu svorio, labiau pasitikėsiu savo kūnu.“ |

| N – Need (Poreikis) | Poreikis keistis, parodyti, kad tai svarbu | „Man reikia pakeisti mitybą, nes mano cukraus kiekis kraujyje yra didelis.“ |

| C – Commitment (Įsipareigojimas) | Įsipareigojimas pokyčiams, atviras pareiškimas | „Nuo šiandien planuosiu visos savaitės valgius.“ |

| A –Activation (Aktyvinimas) | Pasirengimas keistis | „Jaučiuosi pasiruošęs pradėti valgyti reguliariai.“ |

| T – Taking steps (Žingsnių žengimas) | Žingsniai pokyčių link | „Vakar apsipirkau ir nusipirkau sveiko maisto.“ |

Norėdami paskatinti klientą kalbėti apie pokyčius, galite naudoti DARNCATS metodo įkvėptus klausimus.

Klausimų pacientui pavyzdžiai:

- Desire: “How would you like your diet to look in a few months?”

- Gebėjimas: „Kas galėtų padėti jums atlikti nedidelius mitybos įpročių pakeitimus?“

- Reasons: “What would you gain by cutting down on sweets?”

- Poreikis: „Kokie sveikatos pavojai verčia jus galvoti apie pokyčius?“

- Įsipareigojimas: „Ką galėtumėte padaryti šiandien, kad pradėtumėte gerinti savo mitybą?“

- Aktyvavimas (pasirengimas): „Įvertinkite skalėje nuo 1 iki 10, kiek esate pasiruošę pokyčiams?“

- Žingsniai: „Ar jau ką nors padarėte, kad pagerintumėte savo mitybos įpročius?“

Strategijos, kaip sustiprinti kalbėjimą apie pokyčius.

Išgirdus kalbėjimą apie pokyčius, naudinga naudoti metodus, kurie jį sustiprina:

- Teigiamų aspektų išryškinimas: „Puiku, kad galvojate apie savo valgiaraščio planavimą. Ką dar galėtumėte padaryti?“

- Gilesnis apmąstymas: „Kodėl šis pokytis jums svarbus?“

- Apibendrinant paciento teiginį: „Taigi, sakote, kad norėtumėte sveikiau maitintis, nes turėtumėte daugiau energijos ir jaustumėtės geresnės nuotaikos?“

Naudingas būdas įvertinti paciento pasirengimą pokyčiams yra naudoti skalės klausimą. Pavyzdžiui: „Skalėje nuo 0 iki 10, kiek esate motyvuotas pradėti sportuoti?“

Pacientui atsakius, galite paklausti: „Kodėl pasirinkote 6, o ne 3?“

Efektyvaus ir neefektyvaus mastelio palyginimas vertinant paciento pasirengimą pokyčiams.

| Mastelio keitimo tipas | Pavyzdinis klausimas | Kodėl tai veikia arba neveikia |

|---|---|---|

| ✅ Geras mastelio keitimas | „Skalėje nuo 0 iki 10, kur 0 reiškia, kad visiškai nesate pasiruošę pokyčiams, o 10 – kad esate visiškai pasiruošę pokyčiams, kaip įvertintumėte savo pasirengimą sumažinti energinių gėrimų vartojimą?“ | Šis klausimas leidžia pacientui įvertinti savo pasirengimą, skatina apmąstyti ir išvengti spaudimo. |

| ❌ Prastas mastelio keitimas | „Esi pasiruošęs pokyčiams, tiesa? Galbūt apie 8 ar 9?“ | Didelio skaičiaus nurodymas gali sukelti gynybinę reakciją ir atgrasyti nuo sąžiningo atsakymo. |

| ✅ Geras mastelio keitimas | „Gerai, sakei, kad tavo pasirengimo lygis yra 5. Kodėl jis yra 5, o ne 3 ar 4?“ | Padeda pacientui atpažinti teigiamus savo motyvacijos aspektus ir sustiprina kalbėjimą apie pokyčius. |

| ❌ Prastas mastelio keitimas | „Kodėl tik 5? Tau reikėtų norėti daugiau pokyčių.“ | Sukelia kaltės jausmą ir gali sukelti pasipriešinimą pokyčiams. |

| ✅ Geras mastelio keitimas | „Kas galėtų padėti jums padidinti savo skaičių vienu ar dviem punktais?“ | Skatina pacientą pačiam ieškoti sprendimų ir planuoti realius tolesnius veiksmus. |

| ❌ Prastas mastelio keitimas | „Kodėl tau dar ne 10? Tai svarbu tavo sveikatai.“ | Sukuria spaudimą ir neigiamas emocijas, kurios gali užblokuoti atvirą, sąžiningą bendravimą. |

Pokalbio modeliavimas: DARNCATS praktikoje

Kontekstas:

Socialinis darbuotojas kalbasi su jauna moterimi (23 metų Karolina), kuri kovoja su depresija ir vartoja daug energinių gėrimų. Pokalbio tikslas – padėti jai keisti mitybos įpročius, pasitelkiant motyvacinius interviu, pagrįstus DARNCATS metodais.

🔹 D – Troškimas – Noro pasikeisti išreiškimas

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Karolina, minėjote, kad geriate gana daug energinių gėrimų. Ar kada nors pagalvojote, kaip atrodytų jūsų gyvenimas, jei jų gertumėte mažiau?“

Karolina: „Taip… Kartais pagalvoju, kad būtų gerai, jei jų nereikėtų kiekvieną dieną. Galbūt dieną jausčiausi mažiau pavargusi.“

🎯 Technika: Socialinis darbuotojas padeda Karolinai atpažinti jos vidinį norą keistis.

🔹 A – Gebėjimas – Tikėjimas, kad pokyčiai yra įmanomi

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Užsiminėte, kad norėtumėte sumažinti energinių gėrimų vartojimą. Kas, jūsų manymu, galėtų jums padėti?“

Karolina: „Manau, galėčiau pabandyti gerti daugiau vandens arba rasti kitų būdų, kaip jaustis žvalesnei… Bet nesu tikra, ar galiu tai padaryti, nes tai mano įprotis jau seniai.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Tai iš tiesų skamba kaip iššūkis, bet pastebėjau, kad jau turite idėjų alternatyvoms. Tai tikrai svarbu! Kas galėtų padėti jums įgyvendinti tą planą?“

🎯 Technika: Socialinė darbuotoja stiprina Karolinos tikėjimą savo sugebėjimais, pabrėždama jos pačios idėjas.

🔹 R – Priežastys – Konkrečios pokyčių priežastys

Socialinis darbuotojas: „O ką, jūsų manymu, gautumėte sumažinę energinių gėrimų vartojimą?“

Karolina: „Turbūt geriau miegočiau, nebūtų tų staigių energijos kritimų… Be to, žinau, kad tie gėrimai nėra sveiki, o mano kūnas ir taip nusilpęs.“

🎯 Technika: Karolina pati išvardija pokyčių priežastis, o tai sustiprina jos motyvaciją.

🔹 N – Poreikis – Pabrėžti pokyčių svarbą

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Sakote, kad jūsų kūnas nusilpęs ir kad šie gėrimai nepadeda jums jaustis gerai. Kiek jums svarbu dėl to ką nors daryti?“

Karolina: „Manau, kad tai labai svarbu… Gydytojas pasakė, kad man trūksta vitaminų ir kad kava bei energiniai gėrimai gali pabloginti situaciją. Kartais jaučiu, kad turėčiau ką nors dėl to daryti, bet man trūksta motyvacijos.“

🎯 Technika: Socialinis darbuotojas padeda Karolinai suprasti, koks svarbus jai šis pokytis.

🔹 C – Įsipareigojimas – Aiškus veiksmų pareiškimas

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Jei manote, kad tai svarbu, koks galėtų būti jūsų pirmas žingsnis link šio pokyčio?“

Karolina: „Gal pabandysiu per dieną išgerti vienu energiniu gėrimu mažiau ir jį pakeisti vandeniu arba citrinos arbata?“

🎯 Technika: Karolina pati apibrėžia konkretų žingsnį, kuris padidina jos kontrolės jausmą pokyčio atžvilgiu.

🔹 A – Aktyvavimas (pasirengimas veikti) – pasirengimo pokyčiams išreiškimas

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Tai skamba kaip geras planas! Skalėje nuo 1 iki 10, kur 1 reiškia, kad visiškai nesate pasiruošę, o 10 – kad esate visiškai pasiruošę veikti – kaip įvertintumėte savo pasirengimą šiam pokyčiui?“

Karolina: „Galbūt 6. Norėčiau, bet bijau, kad man nepavyks.“

🎯 Technika: Socialinis darbuotojas patikrina Karolinos pasirengimą pokyčiams ir gali paskatinti ją apmąstyti, kas galėtų padidinti jos motyvaciją.

🔹 T – Žengiant žingsnius (pirmieji žingsniai) – imantis veiksmų pokyčių link

Socialinis darbuotojas: „Puiku, kad esate 6 lygyje! Kas galėtų padėti jums pakilti iki 7 ar 8 lygio?“

Karolina: „Galbūt jei turėčiau aiškų planą ir priminimus telefone… arba jei kas nors mane palaikytų.“

Socialinė darbuotoja: „Skamba kaip puiki idėja! Galbūt pradžiai galėtumėte pabandyti užsirašyti, kiek energinių gėrimų išgeriate kiekvieną dieną, ir pažiūrėsime, kaip atrodys per savaitę?“

Karolina: „Taip, galėčiau. Pabandysiu pradėti rytoj!“

🎯 Technique: Karolina clearly begins taking action, which increases her chances of success.

Simuliacijos santrauka:

Pokalbyje buvo naudojamos visos septynios DARNCAT kategorijos:

✅ Noras – Karolina norėtų gerti mažiau energinių gėrimų.

✅ Gebėjimai – ji apmąsto, kas galėtų jai padėti tai pasiekti.

✅ Priežastys – Ji pripažįsta, kad maisto kiekio mažinimas gali pagerinti jos miegą ir sveikatą.

✅ Poreikis – Ji supranta, kad pokyčiai yra svarbūs jos kūnui.

✅ Įsipareigojimas – Ji pareiškia, kad stengsis sumažinti savo vartojimą.

✅ Aktyvinimas – Ji įvertina savo pasirengimą pokyčiams.

✅ Žingsnių ėmimasis – ji imasi veiksmų (stebi savo suvartojamą kiekį).

Kodėl DARNCATS strategija veikia Karolinos atveju?

- Jokio spaudimo – socialinis darbuotojas neverčia Karolinos keistis, o leidžia jai pačiai priimti sprendimą.

- Motyvacijos stiprinimas – kalbėjimo apie pokyčius stiprinimas skatina laipsnišką įsitraukimą į procesą.

- Karolina jaučiasi kontroliuojanti situaciją – ji pati žengia pirmuosius žingsnius, o tai padidina jos įsitraukimą.

1.2.3. Planavimas

Pokyčių planavimas yra paskutinis motyvuojančio pokalbio etapas, kurio metu klientas pereina nuo savo situacijos apmąstymo prie konkrečių veiksmų. Šiame etape labai svarbu motyvaciją paversti realiais žingsniais, kurie yra įgyvendinami ir pritaikyti prie paciento galimybių.

Efektyvus pokyčių planavimas grindžiamas SMART principu, o tai reiškia, kad reikia nustatyti tikslus, kurie yra:

✅ S – (Specific) Konkretūs

✅ M – (Measurable) Išmatuojami

✅ A – (Achievable) pasiekiami

✅ R – (Relevant) Aktualūs

✅ T – (Time bound) riboti laiku

To facilitate the client’s transition from thinking to action, Brief Action Planning (BAP) is used – a planning method based on four basic questions:

Trumpo veiksmų planavimo (VVP) žingsniai

- 1 žingsnis: tikslo nustatymas – „Ar yra kažkas, ką norėtumėte padaryti dėl savo sveikatos?“

Tikslas: pacientas / klientas pasirenka konkrečią sritį, kurioje nori dirbti.

Jei asmuo nežino, nuo ko pradėti, specialistas gali pasiūlyti „pasirinkimų meniu“, pvz.:

„Kai kurie žmonės nusprendžia sumažinti cukraus kiekį savo mityboje, kiti pradeda planuoti reguliarius valgius. Ar jus domina kas nors panašaus?“

Pokalbio pavyzdys:

Terapeutas: „Ar norėtumėte ką nors pakeisti savo mitybos įpročiuose per ateinančias kelias savaites?“

Klientas: „Taip, norėčiau sumažinti energinių gėrimų vartojimą.“

- 2 žingsnis: Įsipareigojimo skatinimas – „Ar galite pakartoti tai, ką norite daryti?“

Tikslas: klientas garsiai išsako savo planą, o tai padidina tikimybę, kad jis jį įgyvendins.

Pokalbio pavyzdys:

Terapeutas: „Puiku! Gal galite tiksliai pasakyti, ką ketinate daryti?“

Klientas: „Noriu sumažinti energinių gėrimų, kuriuos išgeriu kiekvieną dieną, skaičių.“

- 3 veiksmas: Pasitikėjimo įvertinimas – „Kiek esate įsitikinę, kad galite tai padaryti?“

Tikslas: Klientas įvertina savo pasitikėjimą savimi skalėje nuo 0 iki 10.

Jei atsakymas yra mažesnis nei 7, terapeutas padeda modifikuoti planą, kad jis būtų lengviau įgyvendinamas.

Pokalbio pavyzdys:

Terapeutas: „Skalėje nuo 0 iki 10, kur 0 reiškia nepasitikėjimą savimi, o 10 – visišką pasitikėjimą savimi, kiek esate įsitikinęs, kad galite tai padaryti?“

Klientas: „Manau, 5.“

Terapeutas: „Kas galėtų padėti jums pakelti tą pasitikėjimą savimi iki 7 ar 8?“

Klientas: „Galbūt būtų lengviau, jei vieną energinį gėrimą pakeisčiau pipirmėčių arbata arba citrinų vandeniu.“

Terapeutas: „Gera mintis! Galbūt pradžiai pabandykite pakeisti tik vieną energinį gėrimą per dieną?“

- 4 veiksmas: Pagalbos teikimas ir tolesnių veiksmų nustatymas – „Ar norėtumėte suplanuoti konsultaciją?“

Tikslas: Klientas pasirenka, kaip stebėti savo pažangą – pvz., rašydamas dienoraštį, mobiliojoje programėlėje ar tolesnio pokalbio metu.

Paprastas pokalbis:

Terapeutas: „Ar norėtumėte kažkaip stebėti savo pažangą? Galėtume suplanuoti kitą susitikimą arba galėtumėte sekti, kiek energinių gėrimų išgeriate per dieną.“

Klientas: „Manau, užsirašysiu tai užrašų knygelėje, o kitą savaitę galėsiu papasakoti, kaip sekėsi.“

Terapeutas: „Skamba puikiai! Susitiksime po savaitės ir aptarsime, kas pavyko gerai.“

Atvejo analizė – atvejo pavyzdys

Initial Situation:

24 metų universiteto studentė Ana kenčia nuo depresijos ir lėtinio nuovargio. Ji kasdien išgeria 3–4 energinius gėrimus, manydama, kad jie padeda jai susikaupti ir išlaikyti energiją. Gydytojas pastebėjo, kad tai gali pabloginti jos miego problemas ir padidinti nerimą. Ana nori ką nors pakeisti, bet nežino, nuo ko pradėti.

Trumpo veiksmų planavimo (VVP) procesas:

🔸 1 žingsnis: tikslo nustatymas

Terapeutas: „Ar yra kažkas, ką norėtumėte pakeisti savo mitybos įpročiuose?“

Ana: „Taip, noriu sumažinti suvartojamų energinių gėrimų kiekį.“

🔸 2 žingsnis: įsipareigojimo skatinimas

Terapeutas: „Puiku! Kaip tiksliai norėtumėte tai padaryti?“

Ana: „Vietoj 3–4 skardinių per dieną apsiribosiu daugiausia 2.“

🔸3 žingsnis: Pasitikėjimo savimi vertinimas

Terapeutas: „Kiek esate įsitikinę, kad galite tai padaryti? 0 reiškia nepasitikėjimą savimi, 10 – visišką pasitikėjimą savimi.“

Ana: „Galbūt 6… Bijau, kad būsiu pavargusi.“

Terapeutas: „Kas galėtų padėti padidinti tą pasitikėjimą savimi?“

Ana: „Galėčiau pabandyti gerti daugiau vandens ir vieną energetinį gėrimą pakeisti žaliąja arbata.“

Terapeutas: „Puiki mintis! Ar pabandysite tai pakeisti savaitei?“

Ana: „Taip, galiu pabandyti.“

🔸4 žingsnis: Stebėjimas ir palaikymas

Terapeutas: „Kaip norėtumėte stebėti savo pažangą?“

Ana: „Užsirašysiu, kiek gėrimų išgeriu kiekvieną dieną.“

Terapeutas: „Skamba kaip geras planas. Susitiksime dar kartą po savaitės ir aptarsime, kaip sekėsi.“

INTERAKTYVI VEIKLA 44

| Bibliografija |

| Miller, W. R. (2022 m. liepa). Motyvuojantis pokalbis: evoliucija ir naujovės [internetinis seminaras]. Plenarinis pranešimas, skaitytas Kolumbijos socialinio darbo mokykloje. Miller, W. R. ir Rollnick, S. (2013). Motyvuojantis pokalbis: padėti žmonėms keistis (3-iasis leidimas). „The Guilford Press“. Cole, S. A., Sannidhi, D., Jadotte, Y. T. ir Rozanski, A. (2023). Motyvuojančio pokalbio ir trumpo veiksmų planavimo taikymas teigiamo sveikatos elgesio ugdymui ir palaikymui. „Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases“, 77, 86–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2023.02.003 |

1.3. Bendravimo pritaikymas prie kliento kognityvinio ir motyvacinio lygio.

Kognityvinio funkcionavimo lygis – tai yra, kaip klientas suvokia jį supančią realybę, prisimena ir apdoroja informaciją – tiesiogiai veikia tai, kaip jis supranta savo sunkumus ir kaip vertina savo gebėjimą įgyvendinti pokyčius. Kai kuriais atvejais realistiškai įvertinti tiek savo situaciją, tiek gebėjimą atlikti būtinus pokyčius nėra visiškai įmanoma.

Daugelis asmenų, sergančių psichikos ligomis (pvz., šizofrenija, depresija, bipoliniu sutrikimu, nerimo sutrikimais), gali patirti kognityvinių sutrikimų, net jei jie nėra iš karto matomi „iš pirmo žvilgsnio“.

Keičiant mitybos įpročius, tai yra labai svarbu, nes:

- klientas gali nesuprasti rekomendacijų dėl sveikos mitybos,

- jie gali pamiršti, ką ar kada turėjo valgyti,

- jie gali nepastebėti ryšio tarp maisto ir savo gerovės,

- jie gali jaustis prislėgti dėl per didelio informacijos kiekio.

Kalbos ir informacijos pateikimo būdo pritaikymas padidina tikimybę, kad klientas ją supras ir galės žengti pirmąjį žingsnį pokyčių link.

Praktiniai patarimai – kaip koreguoti bendravimą

- Užtikrinkite gerą atmosferą ir sąlygas pokalbiui ir pritaikykite kalbos tempą prie kliento gebėjimų.

🔸 Pavyzdys: jei klientas lengvai išsiblaško, išjunkite telefoną, uždarykite duris, kalbėkite lėčiau ir stebėkite, ar klientas supranta jūsų žinutę.

- Naudokite paprastą, kasdienę kalbą

🔸 Užuot sakę: „Prašau padidinti skaidulų suvartojimą“

🔸 Sakykite: „Pabandykite kasdien suvalgyti obuolį arba riekelę viso grūdo duonos – tai padeda virškinti ir pagerinti nuotaiką.“

- Suskaidykite informaciją į mažas dalis ir pakartokite.

🔸 Pavyzdys: Neperžvelkite viso dienos valgiaraščio iš karto – pradėkite nuo pusryčių.

🔸 Pasakykite: „Kol kas susitelkime tik į pusryčius – rytoj ryte pabandykite suvalgyti ką nors šilto, pavyzdžiui, avižinių dribsnių.“

- Naudokite rašytinius užrašus arba paprastas vaizdines priemones

🔸 Pavyzdys: sukurkite užrašą su klientu, kuriame išvardytos trys sveikų pietų idėjos, ir priklijuokite jį ant šaldytuvo.

- Užduokite patikrinimo klausimus, kad įsitikintumėte supratimu – be vertinimo.

🔸 Pavyzdys: „Ar norėtumėte pakartoti tai, dėl ko susitarėme?“, „Kaip jūs tai suprantate?“, „Ką prisimenate iš šio pokalbio?“

- Suteikite pasirinkimų ir sustiprinkite kontrolės jausmą – nesakykite „privalote“

🔸 Pavyzdys: „Šiandien vietoj kolos galėtumėte pabandyti vandens – ką manote, ar galėtumėte paragauti kartą per dieną?“

- Sustiprinkite ir patvirtinkite mažas sėkmes

🔸 Pavyzdys: „Puiku, kad nusipirkote obuolių – tai svarbus žingsnis. Džiaugiuosi, kad jums pavyko tai padaryti!“

Dažniausių kognityvinių sunkumų pavyzdžiai ir jų reikšmė dirbant su pacientu / klientu:

SOCIALINIO DARBUOTOJO KONTROLINIS SĄRAŠAS

Kaip atpažinti kliento kognityvinius gebėjimus ir koreguoti bendravimą?

(Ypač atsižvelgiant į besikeičiančius sveikatos ir mitybos įpročius)

🔍 I. STEBĖTI – ar klientas…

☐ Greitai nukrypsta nuo temos arba „užstringa pokalbio metu“ – tai reiškia, kad praranda susidomėjimą diskusija?

☐ Reikia daugiau laiko atsakyti į jūsų klausimus?

☐ Dažnai prašote paaiškinti arba pakartoti informaciją?

☐ Užduokite klausimus, kurie rodo, kad jūsų žodžius supratote pažodžiui?

☐ Atrodote prislėgti, kai vienu metu kalbatės apie kelis dalykus?

☐ Atrodo, kad pamiršote anksčiau sutartą informaciją ar susitarimus?

🧠 II. PRITAIKYKITE – pritaikykite savo bendravimo stilių prie kliento gebėjimų

✳️ Kalba:

☐ Naudokite paprastus žodžius ir trumpus sakinius

☐ Venkite medicininio žargono ir sudėtingų terminų

☐ Paaiškinkite bet kokį terminą, kuris gali būti neaiškus

✳️ Bendravimo forma:

☐ Suskaidykite informaciją į mažesnes dalis

☐ Aptarkite po vieną mitybos pakeitimą (pvz., tik pusryčius)

☐ Jei reikia, naudokite popierių, piešinius ar jau paruoštą vaizdinę medžiagą

☐ Pasiūlykite būdų, kaip klientui palengvinti apsipirkimą (pvz., pirkinių sąrašas, planuojamo valgio ingredientų sąrašas)

✳️ Tempas ir stilius:

☐ Kalbėkite lėtai, darydami pauzes

☐ Įsitikinkite, kad klientas neatsilieka, bet jo „neišbandykite“

☐ Suteikite erdvės laisvai užduoti klausimus

💬 III. SUPRATIMO PATIKRINIMAS

☐ Užduokite tokius klausimus kaip:

– „Ką prisiminėte iš mūsų pokalbio / susitarimų?“

– „Kaip suprantate, dėl ko susitarėme?“

– „Ar norėtumėte, kad tai užsirašyčiau?“

☐ Stebėkite kūno kalbą – ar klientas linkteli, bet atrodo sutrikęs?

☐ Venkite klausti „Ar viskas aišku?“ – klientas gali mandagiai atsakyti „taip“.

☐ Paraginkite klientą užduoti jums klausimus, pvz., „Ar norėtumėte ko nors paklausti?“

🤝 IV. STIPRINKITE IR UGDYKITE MOTYVACIJĄ

☐ Pripažinkite kiekvieną pažangą, net ir mažiausią (pvz., „Šiandien išbandėte kažką naujo – tai svarbu!“)

☐ Siūlykite pasirinkimus – neprimeskite paruoštų sprendimų

☐ Paklauskite: „Nuo ko norėtumėte pradėti?“, „Nuo ko jums būtų lengviausia pradėti?“ATMINTINĖ:

Bendravimo pritaikymas nėra susijęs su „palengvinimu“ ar paruoštų sprendimų teikimu, o su tikru supratimu ir veiksminga parama. Dirbant su psichikos ligomis sergančiais asmenimis, aiškus, ramus ir empatiškas bendravimas gali būti labai svarbus jų įsitraukimui ir pasirengimui pokyčiams.

Kliento pasirengimą pokyčiams galima įvertinti naudojant Prochaskos ir DiClemente transteorinį pokyčių modelį, kuris buvo išsamiai aptartas ankstesnėje šio modulio dalyje. Šis modelis padeda suprasti, kuriame pokyčių proceso etape yra klientas – ar jis tik pradeda atpažinti problemą, ar jau yra pasirengęs imtis veiksmų. Dėl to socialinis darbuotojas gali geriau pritaikyti savo bendravimo stilių ir teikiamos paramos tipą prie dabartinio kliento motyvacijos lygio, o tai žymiai padidina tikimybę veiksmingai įgyvendinti pokyčius, pavyzdžiui, pagerinti mitybos įpročius, padidinti valgymo reguliarumą ar sumažinti žalingą elgesį.

| 1 atvejis: Klientas, sergantis depresija ir turintis žemą motyvaciją (prieškontemplacijos stadija) Marekas: 54 metų, jau keletą metų kenčia nuo depresijos. Jis turi mažai energijos, vengia kalbėti apie sveikatą ir nemato prasmės keisti savo mitybos. Jo mityba daugiausia sudaryta iš saldumynų ir greitai paruošiamo maisto. Jis nemato to kaip problemos – „vis tiek nesvarbu“. Adaptuota žinutė: „Marekai, suprantu, kad neturi daug energijos gaminti ir kad išgyvenai sunkų laikotarpį. Kartais nedideli pokyčiai – pavyzdžiui, stiklinės vandens išgėrimas vietoj saldaus gėrimo – gali šiek tiek pagerinti tavo savijautą. Ką apie tai manai?“ Kodėl tai veikia: Žinutė paprasta ir konkreti, vengiama neaiškių frazių, tokių kaip „reikia sveikai maitintis“. Ji nedaro spaudimo – užuot raginęs keistis, darbuotojas skatina apmąstyti. Ji atsižvelgia į žemą motyvaciją ir kognityvinį lygį – siūlomas pakeitimas yra nedidelis ir realus. Pripažįstama kliento patirtis, o tai padeda sukurti pasitikėjimą. |

| 2 atvejis: Klientė, turinti nerimo sutrikimų (apmąstymų stadija) Joanna: 30 metų, kenčia nuo nerimo sutrikimų. Ji supranta, kad mityba veikia jos nuotaiką, tačiau bijo keistis – bijo nesėkmės ir nerimauja, kad „nesusitvarkys“. Jai patinka konkreti informacija, tačiau ji lengvai pasiduoda pervargimui. Adaptuota žinutė: „Joanna, minėjai, kad rytais dažnai jautiesi išsekusi ir išsiblaškiusi. Kai kurie žmonės pastebi, kad ryte suvalgę ką nors – pavyzdžiui, duonos riekelę su sūriu ar košę – pasijunta geriau. Ar sutiktum tai išbandyti dvi dienas ir pažiūrėti, kaip jautiesi?“ Kodėl tai veikia: Darbuotojas nurodo emocijas ir simptomus, kuriuos klientas jau atpažįsta (nuovargis, išsiblaškymas). Žinutė yra konkreti, be informacijos perkrovos ir apima aiškų valgio pavyzdį. Ji suteikia kontrolės ir pasirinkimo jausmą – pasiūlymas „išbandyti“ sumažina nesėkmės baimę. Žinutė tinka apmąstymų stadijai – ji neprimeta pokyčių, o siūlo eksperimentą. |

1.4. Kognityvinės ir emocinės kliūtys įgyjant mitybos žinias.

Įsivaizduokite, kad dirbate su Ela – 48 metų moterimi, kuri ilgą laiką sirgo depresija. Pokalbio metu ji užsimena, kad pastaruoju metu „beveik nieko nevalgo“ ir kad „vėl jaučiasi išsekusi“. Kai pasiūlote kartu suplanuoti sveiką vakarienę, Ela linkteli, bet tada paklausia: „Taigi… ką turėčiau pirkti? Nežinau, kas šiais laikais laikoma sveiku.“ Ji atrodo prislėgta ir sutrikusi. Tai ne noro stoka. Tai barjeras – pažintinis ar emocinis – dėl kurio sunku įsisavinti net ir paprasčiausią informaciją apie mitybą.

Dirbant su žmonėmis, turinčiais psichikos sveikatos sutrikimų, vien „suteikti žinių“ nepakanka – labai svarbu suprasti, kas gali trukdyti suvokti informaciją, ir atitinkamai pritaikyti pokalbio stilių, tempą ir pagalbos tipą. Šis modulis padės jums atpažinti šias kliūtis ir pasirinkti veiksmingas strategijas.

Kognityvinės kliūtys – tai sunkumai mąstant, atsimenant, susikaupiant, suprantant ir apdorojant informaciją. Jos dažnai pasireiškia žmonėms, sergantiems psichinėmis ligomis – kartais visam laikui, kartais laikinai (pvz., depresijos ar psichozės epizodo metu). Net ir turėdamas gerą motyvaciją, klientas gali nesugebėti suprasti, prisiminti ar pritaikyti informacijos apie sveiką mitybą.

Atminkite:

- Klientas gali suprasti mažiau, nei atrodo – linktelėjimas ne visada reiškia supratimą.

- Visada patikrinkite, ar supratote, pavyzdžiui: „Ar galite papasakoti, ką prisiminėte iš mūsų pokalbio?“

- Mažiau yra daugiau – geriau efektyviai perteikti vieną dalyką nei penkis chaotiškai.

Emocinės kliūtys įsisavinant mitybos žinias

Įsivaizduokite Artūrą – 35 metų, kelis kartus gydytas psichiatrijos ligoninėje ir jam diagnozuotas bipolinis sutrikimas. Vieno vizito metu jis noriai kalba apie sveiką mitybą ir sako, kad „reikia kažką pakeisti“, bet po savaitės vengia šios temos, atsidūsta ir sako: „Nėra prasmės, vis tiek to nekeisiu.“ Toks elgesys nėra užgaida – jis kyla iš emocinio barjero, turinčio įtakos jo pasirengimui veikti.

Žmonės, turintys psichikos ligų, dažnai kovoja su intensyviomis, kartais ekstremaliomis emocijomis – tokiomis kaip nerimas, gėda, bejėgiškumas ar nusivylimas – kurios apsunkina naujos informacijos įsisavinimą ir sprendimų priėmimą, ypač tokia asmenine tema kaip valgymas.

Dažniausios emocinės kliūtys ir ką galite su jomis padaryti

Trumpo veiksmų planavimo (VVP) žingsniai

1. Pokyčių baimė

Klientas bijo, kad nesusitvarkys, kad kažkas nutiks ne taip arba kad pokyčiai bus per sunkūs. Jis gali vengti kalbėti apie savo mitybą arba į pasiūlymus reaguoti į įtampą.

Ką galite padaryti:

• Pripažinkite / normalizuokite emociją: „Natūralu jausti baimę – net ir maži pokyčiai daugumai žmonių gali sukelti nerimą.“

• Sumažinkite spaudimą: „Tai tik pasiūlymas – mums nereikia apie tai kalbėti ar pradėti šiandien.“

• Pasiūlykite eksperimentą: „Galite pabandyti tik vieną dieną ir pažiūrėti, kaip jaučiatės.“

2. Žema savivertė ir įsitikinimai, tokie kaip: „Aš to negaliu padaryti“

Klientas netiki, kad gali ką nors pakeisti – jis gali sakyti tokius dalykus kaip: „Man niekada nepavyko“, „Aš nemoku gaminti“ arba „Aš tiesiog nesu tam skirtas“.

Kaip paremti:

• Pabrėžkite mikro sėkmes: „Tau pavyko apsipirkti – tai jau žingsnis į priekį!“

• Venkite pamokslų – kalbėkite palaikydami: „Pažįstu daug žmonių, kurie jautėsi taip pat ir vis tiek pabandė.“

• Pasiūlykite veikti kartu: „Ar norėtumėte, kad parodyčiau, kaip pasigaminti paprastas, sveikas salotas?“

3. Gėda ir baimė būti teisiamam

Klientas gali jaustis nejaukiai dėl savo mitybos įpročių, svorio ar rutinos. Gėda gali blokuoti atvirumą ir paskatinti užsisklęsti savyje.

Kaip padėti:

• Niekada nevertinkite ir nekomentuokite išvaizdos, svorio ar elgesio.

• Vartokite neutralią ir empatišką kalbą: „Gerai, kad apie tai kalbate – daugelis žmonių susiduria su panašiais sunkumais.“

• Užtikrinkite privatumą – įsitikinkite, kad pokalbis vyktų ramioje ir saugioje aplinkoje.

4. Depresija, apatija, energijos trūkumas

Klientas „nori ką nors pakeisti“, bet sako: „Neturiu energijos“, „Nematau prasmės“, „Nesu motyvuotas“. Jis gali pasiduoti dar net nepradėjęs.

Kaip palaikyti:

• Pakoreguokite tempą: „Pradėkime nuo vieno dalyko – pavyzdžiui, pabandykite šiandien pavalgyti šiltą maistą.“

• Paklauskite kliento, kas jam lengviausia – tęskite nuo to.

• Patikinkite jį, kad svarbūs ir maži žingsneliai: „Nereikia visko keisti iš karto – kiekviena smulkmena yra svarbi.“

5. Pyktis arba nusivylimas

Kartais dietos tema gali sukelti pyktį: „Kodėl mes apskritai apie tai kalbame?“, „Neturiu tam laiko“, „Jau tiek kartų bandžiau!“. Tai gali reikšti, kad klientas jaučiasi nesuprastas, spaudžiamas ar prislėgtas.

Kaip reaguoti:

• Nesiginčykite – palikite erdvės emocijoms: „Matau, kad ši tema kelia daug įtampos – galėsime apie tai ramiai pasikalbėti vėliau.“

• Nespauskite – pasiūlykite atidėti: „Ar norėtumėte šiandien pakalbėti apie ką nors kita?“

• Būtinai grįžkite prie temos, kai emocijos nurims.

Atminkite:

- Emocijos yra raktas į pokyčius, o ne kliūtis. Jei jas suprasite, padėsite efektyviau nei bet koks vadovas.

- Kliento emocijų pripažinimas yra pirmas žingsnis siekiant pasitikėjimo ir pasirengimo bendradarbiauti.

- Mitybos įpročių keitimas yra labai asmeniškas reikalas – į jį reikėtų žiūrėti labai jautriai.

INTERAKTYVI VEIKLA 45